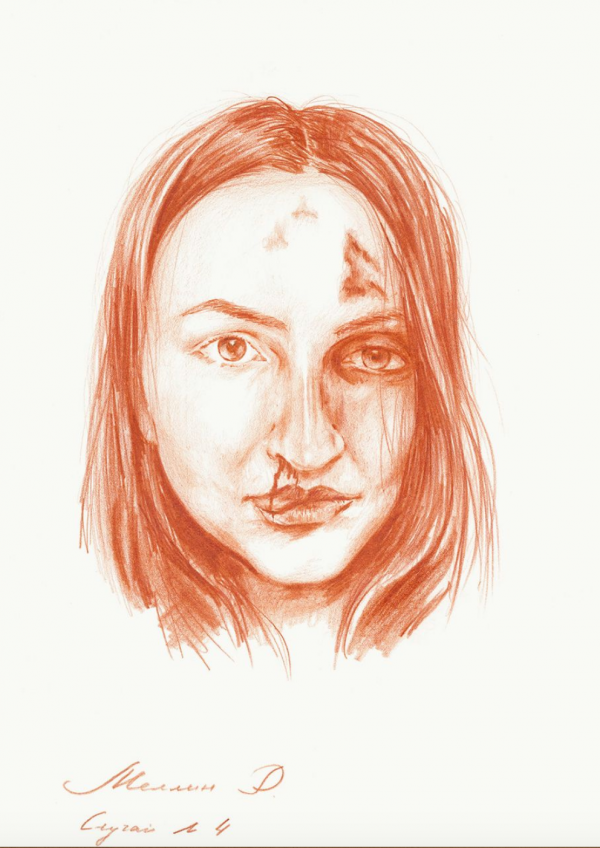

Ruslan Mellin is a facial surgeon based in Siberia who has been treating victims of brutal domestic violence for years—and, more recently, of Covid-19. Art is his salvation and a window onto the humanity of his patients. His drawings have attracted attention in Russia and are now becoming noticed internationally thanks to Meduza, a Russian news site that has profiled him and his work.

“The work was hard and if not for my art, I’m not sure how it would have ended,” he tells The Art Newspaper about the death and despair of 2020, which he has also described in a documentary. “Many colleagues died. Art helped me hide from this horror. Every day at least two or three patients died.”

Lockdown exacerbated the domestic violence he had depicted on the faces of countless female patients and in the rage of their abusers, whom he has also drawn.

“The number of patients with broken jaws, especially women, started to grow,” he said during a late evening telephone conversion after his hospital shift. “Most of them said they had provoked their husbands. These were women with high-level job, bank managers and doctors, with serious injuries.”

A major issue in combating domestic violence in Russia is that the victim is often blamed and takes the blame. “I hope things will change for the better,” Mellin says. “I think this happens because they are degraded and beaten and they think this is how it should be and they are afraid to leave, they think this is normal.”

Kemerovo, the Siberian mining city where he is now based, has in recent weeks become a flash point for Russia’s domestic violence crisis. A man is on trial for beating his girlfriend to death over the course of many hours, while police dismissed neighbours’ calls for help. Legislation from 2017 that decriminalised first-time battery offences has led to a nationwide spike in cases and an activist campaign to repeal the law. Russian government statistics are notoriously imprecise, but studies in recent years count from 5,000 to 14,000 women who die annually from abuse.

The memory of one of Mellin’s early patients, in another city, haunts him to this day. She was an orphan who was taken in by an alcoholic who then brutally attacked her.

“He was drunk and beat her with an axe,” deforming her hands and arms and smashing her face, Mellin says. “The blunt force destroyed her face, her frontal sinus, bone fragments flew off where he hit her against the floor, some covered her eye which went blind.” A significant part of her nose was crushed as well.

Although Mellin, who is 27, studied drawing for years as a child, growing up in a poor family in which his parents had an abusive relationship (“I know about domestic violence because I lived through it”, he says) led him to choose medicine as his profession.

“I loved art, but I understood that if I go into painting I might end up being as poor as my parents and wouldn’t achieve anything in life,” he says.

To protect the privacy of his patients, Mellin draws their wounds, but uses the facial features of fellow doctors.

Now, Kemerovo’s medical university will be hosting an exhibition of his works. A central state art gallery in the city had rejected his works, he says, because a government official learned that he was not a credentialed artist. However, Rossiiskaya Gazeta, a Russian government newspaper, has been sponsoring a touring exhibition of his drawings of Covid-19 patients to libraries in the region. He also posts his works on his Instagram account.

Further afield, Mellin’s works also feature on the website of Licht Feld Gallery in Basel, Switzerland, as an entrant in its Corona Case competition of Covid-themed art.

Fredy Hadorn, the artist who founded the Swiss gallery, describes Mellin’s work as a “combination of the scalpel and the pencil and the stories of the people affected” in a way that is “interesting and shocking also in relation to the home office situation imposed by the virus.” The art highlights that “in many countries, domestic violence is on the rise and leads to outbreaks of violence.”

Mellin has a particular affinity for the works of Van Eyck and Rembrandt, whom he especially admires as a “master of shadow and light.” He has been teaching himself to paint by reading about their technique via his extensive personal library of art books. Mellin recalls art teachers when he was a child who “were breaking me psychologically” by imposing Impressionism as the only acceptable style, and is grateful to another teacher who set him on his current trajectory.

“We had art history, which I loved, with a good teacher, who had a good Moscow education,” he says. “She was the director of our school. She told us in detail about anatomy, about muscles and how they are drawn, and instilled a love for biology. Then in ninth grade, when we were studying human anatomy, I loved looking at muscles in biology textbooks. I think art determined my future profession.”