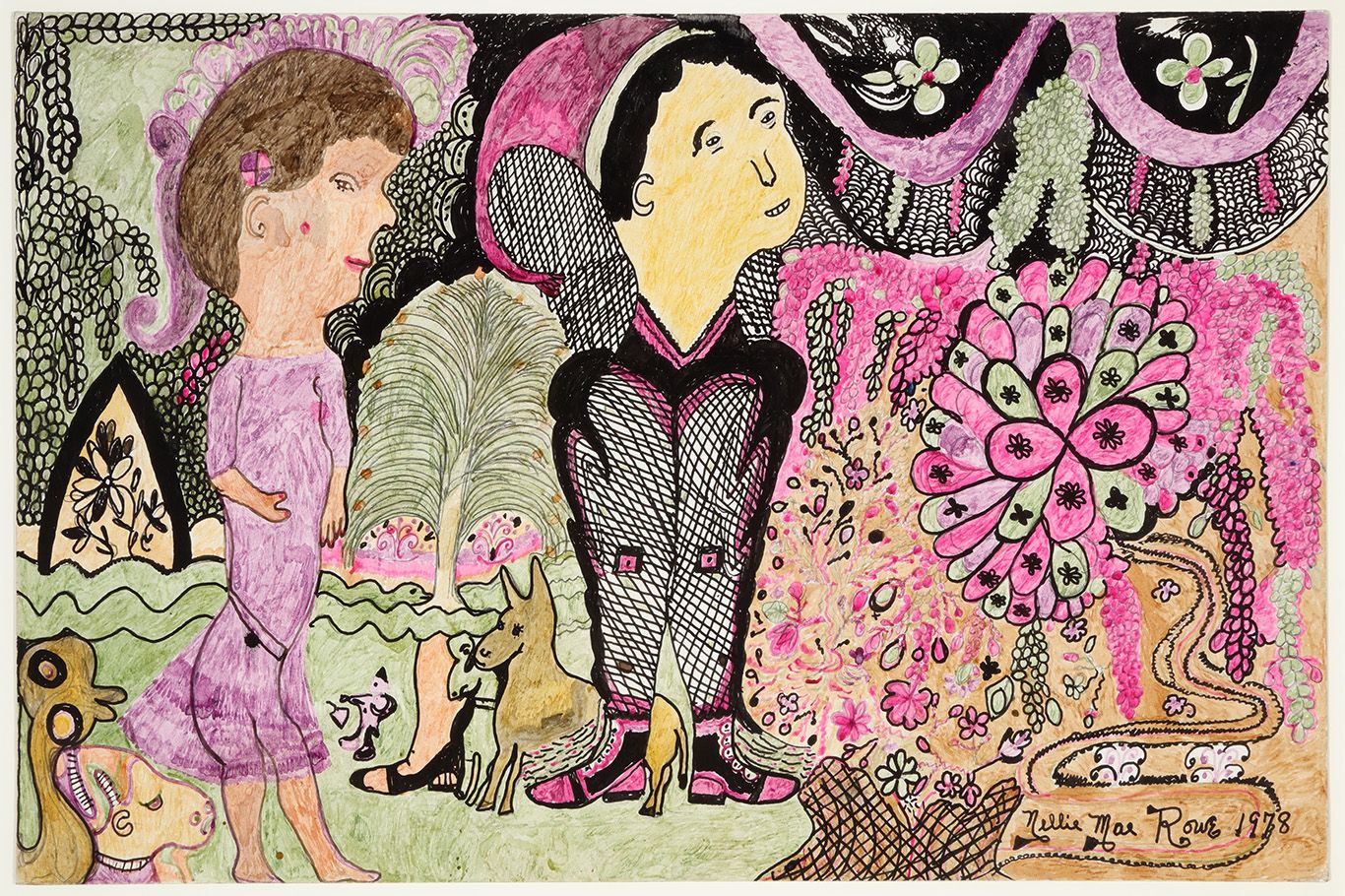

The High Museum of Art in Atlanta today announced a gift of 47 paintings, drawings and sculptures by folk and self-taught Southern artists from a local collecting couple, Harvie and Charles (Chuck) Abney. The donation includes 17 works by the African American artist Nellie Mae Rowe (1900-82), known for vivid colourful drawings brimming with human figures, animals, plants and decorative patterns.

The High says the Rowe drawings gifted by the Abneys will significantly bolster the museum’s voluminous holdings of works by the artist, who also crafted found-object installations, handmade dolls and chewing-gum sculptures in her home. The museum now owns or will inherit more than 200 of Rowe’s drawings and mixed-media sculptures and is planning the exhibition Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe, opening on 3 September and accompanied by a publication.

Rowe worked on a family farm for years and then as a domestic servant before taking up art and eventually welcomed visitors to her tiny home in Vinings, which she called her “playhouse” and turned into a studio. “She was an amazing woman, very self-possessed and self-assured who had a great sense of her value,” Katherine Jentleson, curator of folk and self-taught art at the High, said in an interview. “She died knowing that her art was getting out there. If I could be so bold, I would say she would be very pleased to see herself being valued in this way.”

“Without question, this gift underscores the international importance and distinction of our folk and self-taught collection– in particular, by further highlighting the remarkable contributions of Southern artists,” says Rand Suffolk, the High’s director, in a statement.

The Abneys have pledged to bequeath an additional 26 works by self-taught artists. Highlights of the gift and the bequest also include works by Minnie Evans, Lonnie Holley, Howard Finster and Ronald Lockett.

Evans (1890-1987), an African American artist born in North Carolina, churned out drawings and paintings that evoke a spiritually inspired, surreal dream world populated by curved or twisting plant and animal forms and sometimes human figures and eyes.

“They’re like alien life forms,” says Jentleson, noting that Evans worked as a gatekeeper at Airlie Gardens in Wilmington, North Carolina. “She was exposed to all this botanical life, gardens, symmetrical arabesques, teeming with plant and animal life and organic matter.” The Abneys’ gift and bequest include eight works by the artist.

The current donation also encompasses drawings by Juanita Rogers, Henry Speller, J.B. Murray and John R. Mason, all of them already represented in the High’s collection, as well as art by Archie Byron, described by the museum as Atlanta’s first Black private investigator and known for sculptures and bas reliefs made from sawdust. There are also three sculptures by the African American Tennessee artist Bessie Harvey (1929-1994), a visionary who constructed sculptures out of found objects, especially tree roots and branches.

The sculptures, relatively large, complement smaller works by Harvey in the High’s collection and “this whole tradition of root sculpture, which is so much a part of the American South”, Jentleson says.

The curator points to the abundance of women artists represented in the gift, partly as a result of the tenacity and collector’s eye of Chuck Abney. “That kind of emphasis on the women is unusual–so many of such collections tend to be predominantly male,” she says. The Abneys started collecting folk and self-taught artists in 1980, the museum says, starting with a drawing by Rowe purchased from an Atlanta dealer. “Chuck saw the history of the South playing out in ways they [the couple] hadn’t seen in other kinds of art,” Jentleson says. “They saw that this art was underserved by most institutions and it was affordable and it was local and there wasn’t competition for it. You could get the best of the best.”

Among other highlights of the Abneys’ donation, Jentleson cites a 2016 mixed-media assemblage by the Alabama-born and Atlanta-based Holley, 71, who in recent years became a recording artist. The donated work, whose main element is a plow, honours the agricultural innovations of George Washington Carver (1864-1943), the African American scientist and inventor.

The High owns one of the world’s most important museum collections of American folk and self-taught artists, especially works by Southerners and African Americans. Its collecting in that field began in “fit and starts” around 1975 and then mushroomed as the museum recognised “the extraordinary art in our backyard”, cementing it as a goal in the 1990s, Jentleson says. She assumed her curatorial post in 2015.

As milestones, the museum cites its 1982 acquisition of 30 drawings by the then-obscure but now renowned outsider artist Bill Traylor, who was born into slavery but then spent most of his life as an Alabama sharecropper; a 1994 collaboration with Howard Finster, who transformed his Georgia property into the art environment Paradise Gardens; a 2003 gift of 130 works by Rowe; and a 2017 gift-purchase with the Souls Grown Deep Foundation that added 54 pieces to the institution’s holdings of self-taught artists.

Jentleson suggests that while such artists are now avidly recognised, more could be accomplished: Rowe, for example, “certainly hasn’t been recognised in her fullness yet”. Such artists are “really responding to the historical moments they’re living in,” she emphasises, “even if they don’t run in fine art circles.”