“COVID this way,” read a faux road sign across from Sky Bar and Southeastern on Aug. 28, with an arrow pointing toward the two establishments.

While some students returning to Auburn in August took to downtown bars to party, some of their peers were dismayed. The mind behind the sign, Rose Williams, junior in theatre, was one of them. But rather than using social media to express herself, she used some more traditional artistic media.

“It started off with me being really upset with how the [University] was handling COVID,” Williams said. “I took a class last semester … with a visiting artist from New York, Esteban del Valle. He taught a mural painting class, and in that class, he also taught us about graffiti. That put that idea in my mind of ‘What can I do about this situation?’ He didn’t teach us how to graffiti, he just showed us what [we] can do but did not encourage it.”

Something of a lone wolf artist, Williams has produced several protest art pieces of her own volition since classes resumed for the fall. Her pieces criticize fellow students’ response toward COVID-19 and show support for racial justice demonstrations stemming from the death of George Floyd, a Black man killed by police officers in May in Minneapolis.

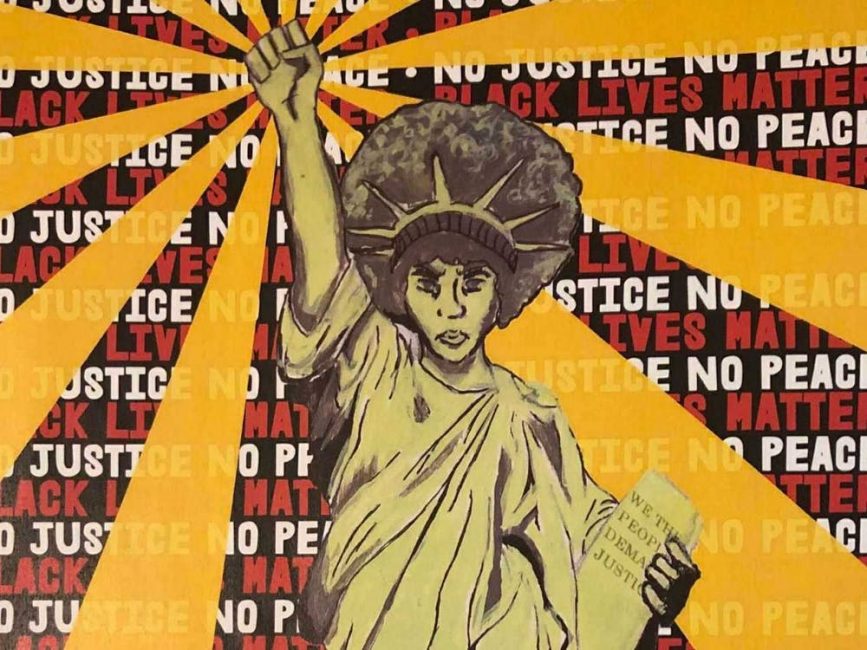

Williams’ creations up to this point have included the road sign, a banner reading “Party till you drop – everyone else dead” that shows a hospital bed and posters displayed around campus featuring an illustration by Williams of a Black woman in the form of the Statue of Liberty. The woman replaces the original statue’s torch with a raised fist and holds a book reading “We the People demand justice” as she stands in front of a background with the phrases “No justice, no peace,” and “Black Lives Matter.”

Taking cues from del Valle, Williams said she has sought to create pieces that do not vandalize property but instead draw attention by having a physical presence.

“Art has always been a medium for me to express myself in a way that words necessarily don’t,” she said. “I feel like, ultimately, [people] won’t listen until you put something in their face. It really gets the message out to people in general … instead of just drawing art online and posting it online.”

Each piece of art has had its own background process in design and method of distribution. For the racial justice protest posters, Williams said she and her boyfriend were up late one night and into the early morning placing them around Auburn’s campus.

“We stayed up from [midnight] to 5 a.m. putting them all up – it took quite a while and quite a bit of walking,” Williams said. “We covered the entire campus, we covered the dorms, pretty much every building that we could.”

Posters, she said, take longer to set up in a situation where she is “trying to get in and get out as fast as [possible]” to avoid any potential legal repercussions vs. the banner or COVID sign which are standalone displays of art and therefore quicker and easier to place.

The posters came in the wake of an AUFAMILY.com Instagram post which reads “Black Lives Matter” surrounded by names of Black Auburn football players. Williams said the post received some opposition in the comment section which furthered her motivation to complete the project.

“There’s already a small percentage of the school who are people of color, and if the mass majority of students do not support the movement, that could definitely feel hostile,” she said. “I wanted to do something that they would see that maybe would make them feel better [and] bring light to the movement.”

Williams, a native of Huntsville, Alabama, said she grew up around people of a variety of backgrounds and identities as the child of a military family, but she noticed a drop in diversity upon moving to Auburn for college.

“I went to a pretty evenly split [high] school, it was a pretty even demographic across people of color and white people,” she said. “Even in Huntsville, it’s pretty disheartening to see the Black community suffer there severely. I haven’t been in touch with the community here because it’s mostly white people in my classes.”

Before creating her protest art, Williams said she consulted with friends of color she has who are aware of her work to ensure it does not negatively impact Auburn’s Black community.

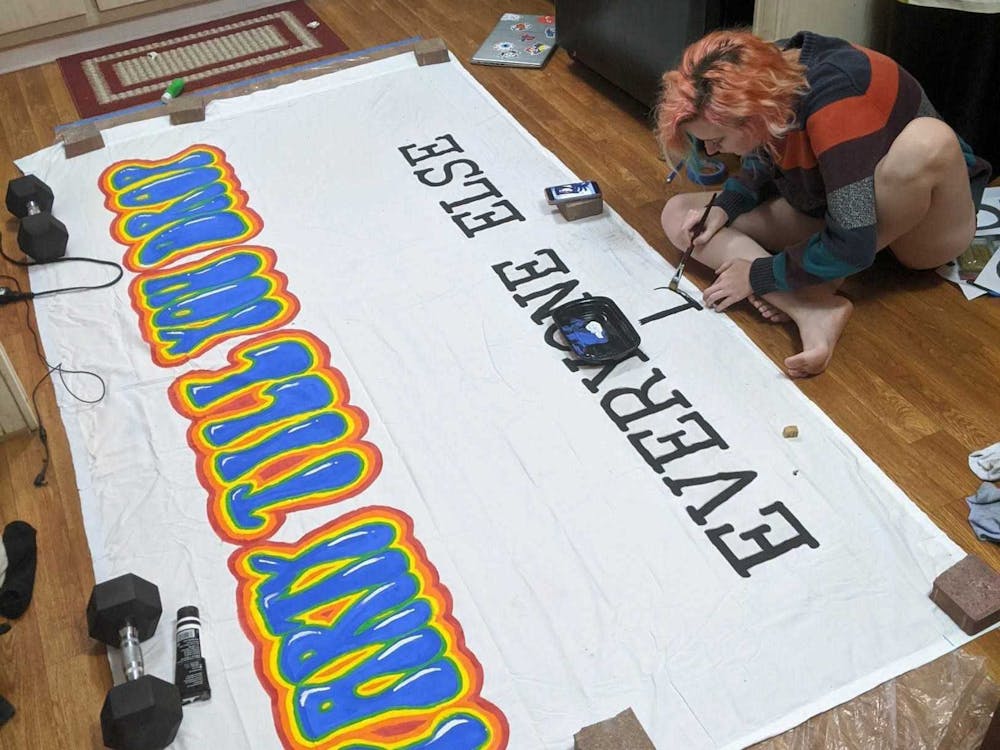

The “Party till you drop” banner was a single piece Williams draped over the main Auburn University sign in front of Samford Hall on Aug. 24 after she felt students were turning a blind eye to recommended COVID-19 safety measures, like physical distancing and wearing masks.

“There’s a fraternity house behind my apartment, and they were having parties night after night after night,” Williams said. “It wasn’t just the noise, it was just the fact that it’s the first week back of school, we’re all trying to social distance and people were going crazy.”

Williams estimates painting the banner, which used a white bedsheet, took her around 20 hours that weekend. To anchor it to the University sign, she laid bricks on each corner of the sheet as not to damage the sign and so that the banner would be easy to remove.

“My back hurt a lot,” she said with a short laugh. “My anger really pushed me through that one. When you do something that big, you’re supposed to staple it to a wall … but I just did it on my floor.”

Of Williams’s three projects, she said the banner has decidedly received the most social media attention, attracting nearly 1,400 likes on a post on her Instagram page. She considers herself a fairly open, public person, but noted that it far exceeded the recognition she anticipated.

“That kinda blew up, more than I was hoping it to,” Williams said. “Most of it was positive. People were really happy I did that, and they were encouraged by it,” Williams said.

Most recently, Williams placed a poster adjacent from Toomer’s Corner imploring passersby to “Wear a Damn Mask” ahead of Auburn’s first home football game against Kentucky, when more visitors arrived in town.

“This one’s for people who think just because it’s football season, COVID went away,” Williams said on an Instagram post of the project on her page. “It’s still here, and you’re making it worse.”

For her next project, Williams is considering taking on downtown bars again, which she said have continued to see large numbers of patrons into September. Another avenue she is looking at is a recent involuntary drugging at a fraternity-related gathering Auburn students were notified about via a campus-wide email sent Sept. 11.

“It was basically just like, ‘Hey, this happened [but] we’re not going to tell you which fraternity did this or who did this; just be careful and cover your drink,’” Williams said. “It didn’t really help anyone. I don’t like how they’re handling that situation. How many women here do get date-raped and drugged?”

Williams did concede that the University may be unable to release any names for legal reasons “without solid proof,” an aspect she said would need to be taken into account if she approached the subject for her work.

“I’m not going to do anything to slander [the University],” she said. “Legally, I’ve had my boyfriend help me out a lot with this, so if I do get in trouble it’ll be as little as possible. I still want to go to Auburn, I still want to finish my major.”

One of the greatest tests of courage Williams said she faces in making protest art is toeing the line of legality in displaying her work, challenging how and where she can express her freedom of speech. On top of the legal questions, Williams said she knows that some people are always going to disagree with her type of art.

“Protesting is never something that you get permission for, you’re always going to get backlash,” Williams said.