This article initially began with the words “We have failed.”

I was burning up at the mind-numbing lack of compromise between party lines, pained by the inability of neighbor to love (or at least respect) neighbor, and stunned at the election of a man who ran a campaign flooded with hateful, destructive rhetoric. I was plagued with questions, but certain that artists and arts institutions across the nation had let the populace down. The stunning lack of empathy on display, both during and after our election, evidenced a citizenry more interested in nationalism and self-interests than in unity.

It has become clear to me in the months since the election that the crushing disappointment I was feeling was shared, and that it has become a springboard for theatrical action.

And empathy is the theatre maker’s job.

It felt as though we’d been stroking ourselves too long, patting ourselves on the back too much. We had allowed ourselves to commodify the arts, bending our noses to our bottom line, and letting our audiences become complacent, our theatre downright masturbatory…

But it has become clear to me in the months since that the crushing disappointment I was feeling was shared, and that it has become a springboard for theatrical action. More and more artists are turning their frustration with the current political climate into fuel for their creative machines.

So I no longer want to begin this article with disillusionment, because I no longer feel disillusioned. I feel emboldened, inspired, and (for the first time in a long while) I feel hopeful.

Hopeful that theatre institutions are digging deep and looking for ways to build bridges instead of walls.

Hopeful that the skepticism (of “fact,” of the media, of one another), anger, indignation, and hurt on our neighbor’s faces is only temporary.

Hopeful that the America we now see—the one tearing itself apart trying to “fix” its varied wounds—will succeed in its attempts to heal.

But nothing will change until we start listening to one another again, and no one seems to want to start listening to one another without first being heard themselves.

MR. K: You don’t know my pain!

V: My pain! MY PAIN! Look at me! This is torture!

MR. K: Look at you? But what about this? THIS torture!—The Low Tide Gang

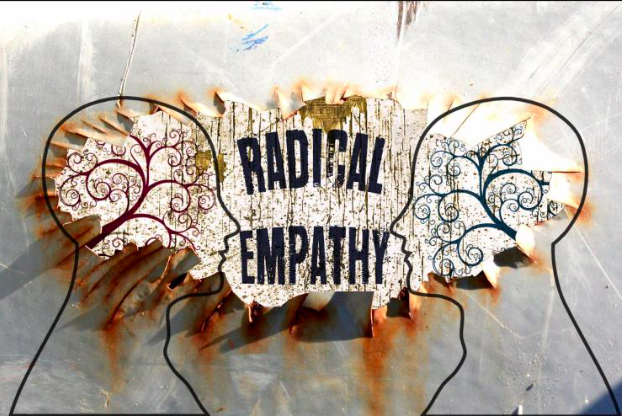

Which is why it will take incredible patience and immeasurable love to push through our own hurt in order to honor the hurt of others. It will take time and dedication. It will take radical empathy.

Radical empathy, as I define it, is the act of reaching out with an open heart and mind, even if we feel the person or community we are reaching out to is undeserving of such openness. It’s the notion that, if we swallow our own hurt long enough to extend empathy to our opposition no matter what (that’s the radical part), we will establish connections capable of yielding far greater fruit than any amount of soap-boxing or condemnation ever will.

Radical empathy is how the artist and arts institutions will foster communication and connection across communities.

Radical empathy is the artist’s new job.

Radical empathy is how the healing will begin, and it will begin with us, now.

“Nothing is easier than to denounce the evildoer; nothing is more difficult than to understand him.”—Fyodor Dostoevsky

As theatre artists who put ourselves in other’s shoes daily, we are uniquely positioned to take on this challenge. Which is why we must lead the charge.

And yes, there will (and must) be art made in protest. I’ve just launched a new project (ProtestPlays.org) dedicated to connecting playwrights with resistors in the hopes of fostering continued opportunities for theatrical action. So I’m not saying we can’t do both… I am saying that without radical empathy outreach, our protests will serve only to bolster shared rage and further alienate those with whom we disagree.

Therefore, we must get to work not just at making powerful art, but also at listening to and making powerful art with/for those who need it most.

Theatre has long been a way station for the ostracized and “other,” but it is also a place where personal politics don’t mean as much as togetherness does, so let us extend this call to our opposition here at home so that they feel welcome in our creative houses.

Welcome to watch.

Welcome to ask questions.

Welcome to connect.

Some suggestions for how to meet and welcome each other in our creative houses:

1. Initiate a discussion within your community.

A few years ago I was invited to a salon at a local restaurant in my hometown of Prescott, Arizona. The salon was a monthly opportunity for twelve strangers to get together and discuss current events—the emphasis being that we were there to practice civil discourse. There were appetizers, there were drinks, and there were lots of opinions—but because of the sincerity of the organizer’s motivations, we were respectful, engaged, and patient with one another. It was a delightful evening of conversation held on a monthly basis.

My suggestion is that we begin doing something similar at our theatres, art centers, universities, coffee houses, etc… The beautiful thing is that a salon can meet up literally anywhere. As long as there’s food, constructive and civil discourse, and the dedication to make this happen, it can and will.

A few tips:

Invite diverse members of the community to your event—seek out different-minded people. Tell them that your theatre has set an intention of cultivating constructive discourse within your community and that your hope is that by listening to and discussing plays, community members will be able to better connect with and understand one another.

You may want to start out with a salon for community leaders. Invite them to discuss how you/your institution can work with them/their organization/business to become a community unifier. What are some of the concerns they see in the community/their clients/their parishioners? What ideas do they have for fostering connection with community members through art?

Make food part of the equation. There’s a reason we “break bread” together—it is much easier to connect with people over a meal. Consider establishing a partnership with a local restaurant(s) that supports your mission.

Whether you hold the event at a restaurant, a park, or your own green room, the important thing is to mix, mingle, and break through those invisible walls—avoid setting up your salon space like a theatre. Everyone should be in the “creative crock pot” together.

Decide how you want your salon to operate. Ground rules are important (Mutual respect and radical hospitality are key, as is the option for anyone to take a break should they feel themselves getting heated) and it’s important to set clear goals for everyone (“We’re here to practice the art of civil discourse!”) so that all parties know what they’ve been invited to do.

Break into groups of three to four for each portion of the salon.

Split the event into a few different themed segments (idea: The Arts, Local News, Current Events, Unity, etc.) Whatever your topics, it’s good to have a set time limit for each segment, and to rotate speaking groups between.

Another consideration would be to let guests fill out cards with suggested topics fitting each theme, with the host drawing a card for each segment.

Finally, come back together as a whole for a short debriefing. Check in with attendees. Ask “How was this process for you?” This is an opportunity for them to consider and share their experiences with the group, as well as give feedback to you in a way that will help you structure future events.

Make sure to plan for unstructured mingling time after!

Have at the helm a moderator capable of guiding attendees with respect and open-mindedness. Make sure they are able to guide each salon with an indefatigable sense of radical empathy. You will need patience, compassion, and a teacher’s insight to help you maintain a productive and inclusive vibe—and you must not ever enter into a salon with a political agenda. The goal should always be to increase communication across political/social/ideological/economic boundaries.

Watch your language… and I don’t mean expletives! One of the biggest divisions this past election was education levels amongst voters. Try to keep language clear, recognizable, and understood. Select and discuss topics in real world terms as opposed to strictly academic. You can start with the name of your salon: Common Grounds would probably be a welcoming name for a coffee themed gathering. Sociopolitical Intersections probably would not.

Be tenacious. It may take a while to get people involved. That’s okay. It’s probably better to start out small anyway, and let the group grow/evolve from there.

2. Partner with other nonprofits

How many theatre outreach programs are successfully reaching everyone? My guess is not many—it’s nearly impossible to touch a whole community on your own. There will always be members of your city/town that remain outside your particular sphere. But partnering with organizations that serve different members of your community is an excellent way to grow your audience.

My company, Little Black Dress INK (LBDI), produces a nationwide female playwright’s festival that depends on partnerships with producers and other arts organizations across the country. It’s amazing what you can accomplish when you reach out and ask people to jump on board.

In addition to my work with LBDI, I’ve conceived of and produced community-driven festivals with The@trics Theatre. One of my favorite examples of such a festival was a short play festival we created to support the Coalition for Compassion and Justice (CCJ) in Prescott, Arizona. They’re a poverty relief organization focused on helping unemployed people learn job skills that will help them get back to work. They also operate a thrift shop which helps fund their organization.

For the joint festival, we purchased items from the thrift shop, challenged playwrights to write short pieces about them, and then produced the results. We also auctioned off the items—which now had rich stories to go with them—and raised a lot of love, enthusiasm, and cash for the CCJ and also helped to fund our teen theatre workshops.

The beautiful thing was that much of our audience for this event came from the CCJ. They loved the festival and wanted to see more events like it! The project made everyone feel good. On top of that, both organizations made connections with people they otherwise didn’t have access to, increasing visibility and accessibility.

By blending our contact lists, we were able to grow our audience and the CCJ met new community partners. It was a win-win for all, and while it was a lot of work, it took very little in the way of financial resources to make happen.

Of course, this is just one potential avenue to explore—the important thing is that by dedicating ourselves to a theatrical event that served our community above and beyond simply entertaining them, we made art that had an immediate impact on our community, engaged new audiences, and established a healthy partnership between organizations.

3. Get your hands dirty!

You know what else is a great way to share different points of view across socio-economic and political lines? Education.

Theatres may not be able to offer the kind of education you can receive on a college campus, but we can create nurturing, diverse, and engaging environments for learning. Writing workshops, ensemble workshops, acting workshops… Art-making workshops of all kinds provide environments conducive not only to learning, but to sharing as well. Presenting new audiences opportunities to connect with new people through the safety of an expressive workshop is a tremendous opportunity for radical empathy and exchange to happen!

Remember: Don’t just leave workshop participants hanging either—present their finished work, listen to their finished work, learn from their finished work. You’ll all be better (and better connected) for it!

4. Get out of the house!

And by house, I mean the theatre.

There are a lot of people out there who never go to the theatre, aren’t going to go to your theatre, and yet could probably really benefit from seeing good theatre. We’ve got to find ways to get it to them! Theatre tickets are expensive, gas is expensive, babysitters are hard to find, and a lot of the time the material we’re producing isn’t nearly as exciting to the uninitiated as it should to be. So:

Bring the theatre to them.

Bring the readings to them.

Bring the workshops to them.

Bring the salons to them.

Do it.

Do it.

Don’t let geography or outreach be an obstacle.

Just do it.

Art should instigate. It should provoke. It should motivate people to think, to feel, to take action… There are a great many theatres selecting work based around what will be most easy for them to sell rather than thinking about what kind of theatre is most needed now.

Theatre does not need to take place in our hallowed theatrical temples—it can happen anywhere. Perhaps you can’t remount a full production of your theatre’s shows at the Boys and Girls Club, but you can certainly do a reading, a workshop, or a concert from whatever musical your theatre is currently working on in just about any empty space.

5. Plan a season that matters.

Art should instigate. It should provoke. It should motivate people to think, to feel, to take action… There are a great many theatres selecting work based around what will be most easy for them to sell rather than thinking about what kind of theatre is most needed now. Setting the intention to incorporate pertinent, sometimes uncomfortable shows in a season is a great way to shake thing up, open a dialogue, and engage in a little theatrical activism.

Some theatres might have an easy time with this, others may not: the important thing is to try. Try working at least one socio/politically challenging piece into your line-up (and what is “challenging” will be different for every theatre). The key is to commit to producing something that—even if it makes you uncomfortable—reaches out to the “opposition.” Then make sure to create space to discuss the piece with your audiences afterward. Plan a salon series around your shows! Not only is this a great way to foster discussion within the community, but it’s a great way to get feedback from ticket buyers.

Still, if you’re not ready to take a risk with your mainstage productions, there’s another way you can start to get “radical.”

6. Create a reading series focused on presenting and discussing challenging plays

Readings series are super easy—you can read anything, anywhere, and the more casual the setting, the better the conversation afterwards. Coffee shops, art galleries, book stores, a picnic at the park… all of these are great places to step into someone else’s theatrical shoes for a bit and then start a conversation.

“Art is a ripening, an evolution, an uplifting which enables us to emerge from darkness into a blaze of light.”—Jerzy Grotowski

If we as artists can implement just one of these tactics in our communities, we will be well on the road to creating constructive dialogue.

And constructive dialogue is what it’s all about.

As I was putting the finishing touches on this article, a nationwide Twitter war erupted over the cast of Hamilton using their stage as a platform to address vice-president elect, Mike Pence. Their message was articulate, respectful, and delivered in the spirit of fostering connection. And yet, our president-elect’s response was to bemoan the loss of theatre’s “safety,” demanding that the cast apologize for exercising their constitutional right of free speech.

But you and I know the truth: theatre is never safe.

And while our creative homes must remain refuges for all, they mustn’t operate as mere entertainment-havens for our audiences.

We must resist the urge to retreat to the comfort of our like-minded brothers and sisters of the theatre, and instead we must actively invite strangers to our table. We must roll out the welcome mat! For it is only through extending radical empathy and genuine hospitality during these very uncomfortable times that any of us can hope to come out of the other side of this dark tunnel we now enter.

Article Courtesy of: howlround.com