“There won’t be a a penny that is going out the door that is not contributing to a more fair, more just, more beautiful society,” Alexander says.

by Sarah Cascone on July 2, 2020

When future applicants seek funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the largest supporter of the arts and humanities in the US, they will be evaluated based on one principal question: would their proposal help create a more just and fair society?

The organization announced Tuesday that it is reorienting its grant-making program entirely through the lens of social justice. Rather than a wholesale shift, “I would call it an evolution,” Mellon president Elizabeth Alexander told Artnet News, adding that the change has been in the works since she came to the post two years ago.

Current events—both a global health crisis that has disproportionately affected people of color, and widespread Black Lives Matter protests in cities across the US—“only further confirmed the unhealed racial crisis in this country,” making this shift in priorities all the more essential.

“We were going to do it anyway,” Alexander said, but “this moment for the strategic rollout has come at a time for the country where it seems very clear in a much more widespread way that we all need to be thinking very sharply about how the work that we do contributes to a more just society.”

The move echoes the Ford Foundation’s 2015 decision to direct its grant making exclusively toward fighting inequality in 2015. Alexander came to Mellon from the Ford Foundation, and considers the two organizations “siblings in philanthropy.”

So too, the foundations’ focuses on inequality and social justice are closely intertwined. “We live in a culture where resources are unequally distributed,” Alexander said. “Addressing that inequality is another way of talking about what does it mean to contribute to a more just society.”

And just as Ford has continued to support the arts and culture, so, too, will Mellon. “The way that we’re interpreting social justice is very broad,” she said. “It’s very important to Mellon in all of our grant-making to say, ‘Who haven’t we reached? Who haven’t we supported? Who hasn’t felt Mellon was interested in their work?’ … We sit atop tremendous resources that are meant to be shared.”

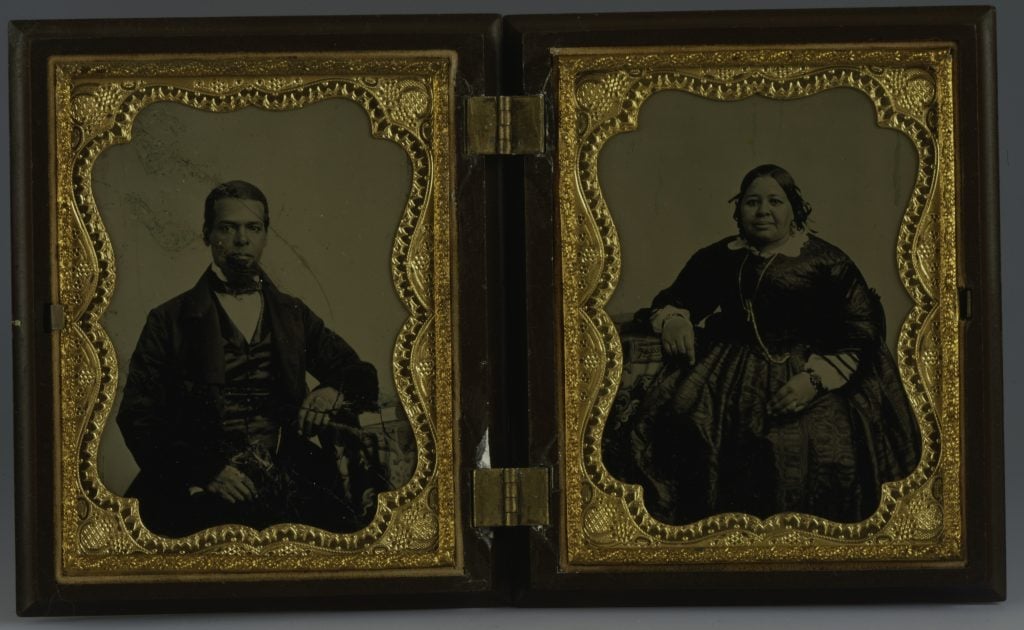

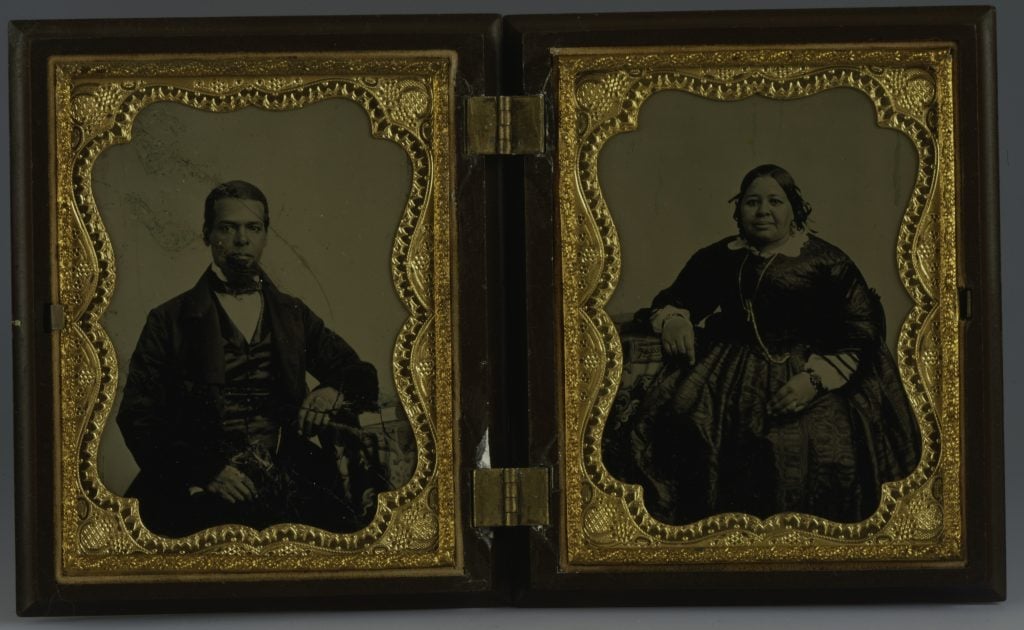

Under the new guidelines, there will be more funding for projects like the $250,000 grant for the Lyons Seneca Village Monument, announced last fall. Mellon is one of four private foundations paying for the $1.15 million sculpture in New York’s Central Park, honoring Albro Lyons, Mary Joseph Lyons, and their daughter Maritcha Lyons. The abolitionist family were property owners in Seneca Village, a Black and immigrant community evicted to make way for the park.

Other recent grantees that fit the social justice purview include NXTHVN, the nonprofit arts incubator artist Titus Kaphar is building in New Haven, Connecticut, and Los Angeles’s Underground Museum, founded by the late artist Noah Davis in 2013.

“They are artist-visioned, -created and -run spaces,” said Alexander, noting that both are also in neighborhoods that don’t have other arts and culture spaces. “We believe that existing institutions can do wonderful work, but it’s very important for us to look at and support institutions that are nascent and that have diverse leadership.”

Mellon is “on the lookout always for people who are trying to grow something new but who have been historically under-resourced,” she added. “Of course, that often means organizations presenting the work of or are run and directed by people of color.”

Installation view of “Rodney McMillian, Brown: videos from The Black Show” at the Underground Museum. Photo by Zak Kelley courtesy of the Underground Museum.

Alexander didn’t mention any specific types of projects that don’t align with Mellon’s new vision, but museums that are stuck in the traditional canon of Western art, with a myopic focus on white male artists, likely won’t make the cut. And the foundation isn’t just looking at programming, but also at museum staff and leadership, recognizing the importance of diversity at all levels—a 2015 Mellon study found museum staff to be overwhelmingly white.

“An institution that remains unaware of the contributions and the excellence and the beauty and the beauty and the ideas and the knowledges of the majority of our population is not serving its community well,” Alexander said.

The Mellon Foundation has ramped up its giving from roughly $300 million annually to $500 million this year, recognizing that artists and cultural organizations have been hard hit by the financial downturn. That’s included helping forge an Artist Relief coalition making 100 grants of $5,000 each to individual artists—who are not normally eligible for Mellon grants.

“I feel like artists are the essential workers for the soul,” said Alexander. “We don’t have an art ecosystem if we don’t have individual artists.”

Mellon has also teamed up with the Ford Foundation and three other foundations to boost its annual giving to nonprofits in dire financial straits due to lockdown, putting $200 million toward the collaborative $1.7 billion effort.

“It is really humbling when you look at all the need and realize ‘we give away the most and it still doesn’t even begin to be enough,’” said Alexander. “We need the arts to take us through dark times. We need the arts to help us imagine a different future.”